Factsheet

Wildlife Areas for Schools

Schools that have begun to develop their grounds often report that this has led to beneficial changes in relationships and attitudes and to the atmosphere of the school in general.

Why create school wildlife areas?

Traditionally, school buildings have been surrounded by rather grim landscapes, particularly those in built-up areas – which account for the majority of schools in Britain. It may seem a daunting task to embark upon a development programme for transforming a square of asphalt into a richly diverse landscape with trees, ponds, flowers, seats, grass, animals etc! However, the long-term benefits of such a scheme will make all the effort involved well worthwhile.

Traditionally, school buildings have been surrounded by rather grim landscapes, particularly those in built-up areas – which account for the majority of schools in Britain. It may seem a daunting task to embark upon a development programme for transforming a square of asphalt into a richly diverse landscape with trees, ponds, flowers, seats, grass, animals etc! However, the long-term benefits of such a scheme will make all the effort involved well worthwhile.

When the decision to go ahead with the development has been made, the next important task is to involve as many people as possible in the design, management and educational use of the grounds – pupils, teachers, caretakers, ancillary staff, parents, governors, community groups and others can all contribute ideas and expertise to such a venture.

Establishing a wildlife area provides many opportunities for extending classroom activities. If the pupils are involved in the creation and maintenance of such an area they learn to respect the hard work and skill necessary to produce and maintain an attractive environment. It should also give them a sense of pride and achievement – and hopefully will encourage them to develop a life-long respect for the environment in general. Apart from the benefits to the school itself, some satisfaction can be felt that another small but safe habitat has been provided for Britain’s dwindling wildlife!

Many areas of the curriculum may be covered in the planning and making of a wildlife area. In Maths the children can solve real problems involving estimation, measuring and calculating surface areas. Map work can be undertaken, such as drawing plans and making scale drawings and scale models when designing the pond area. There are opportunities to carry out research on food chains, food webs and other principles of ecology. Some children may become interested in the conservation aspects of the project, leading to work on endangered species and the effects that humans have on the environment, such as picking wild flowers and using agricultural chemicals.

Many areas of the curriculum may be covered in the planning and making of a wildlife area. In Maths the children can solve real problems involving estimation, measuring and calculating surface areas. Map work can be undertaken, such as drawing plans and making scale drawings and scale models when designing the pond area. There are opportunities to carry out research on food chains, food webs and other principles of ecology. Some children may become interested in the conservation aspects of the project, leading to work on endangered species and the effects that humans have on the environment, such as picking wild flowers and using agricultural chemicals.

Financing the project

Once the site of the wildlife area has been decided on, the next stage is to apply for financial help! Head over to our Roots to Green Living resources page to find out more and find links for funding.

Once the site of the wildlife area has been decided on, the next stage is to apply for financial help! Head over to our Roots to Green Living resources page to find out more and find links for funding.

It may be possible to obtain a grant from the local authority. A county council, city council or London Borough usually has a number of officers responsible for local environmental management, and a conservation officer will probably be very happy to help out with advice as well as, hopefully, financial assistance! Find out from the town hall if the local authority has an environmental co-ordinator, a person responsible for developing and co-ordinating environmental matters across all departments, you can contact.

Designing a Wildlife Area

Almost any land can be converted to a patchwork of vegetation suitable for all sort of projects as long as there is enough enthusiasm for the work. If the school has a playing field or garden, even an edge or corner can provide a useful site. In general, there are two types of site: those where existing features (walls, lawns, shrubberies etc.) can be used, and the sites where there are no features to use. While it is often both possible and preferable to retain existing trees and bushes, it may sometime be best to do away with them in the interest of developing the whole area. For example, one of the best ways to treat a poor, gappy hedge is to cut it to ground level and plant in the large gaps, so that there is uniform vigorous regrowth. Similarly, trees and shrubs which are growing too near walls or which are damaged or diseased are often best removed and replaced with more suitable plants.

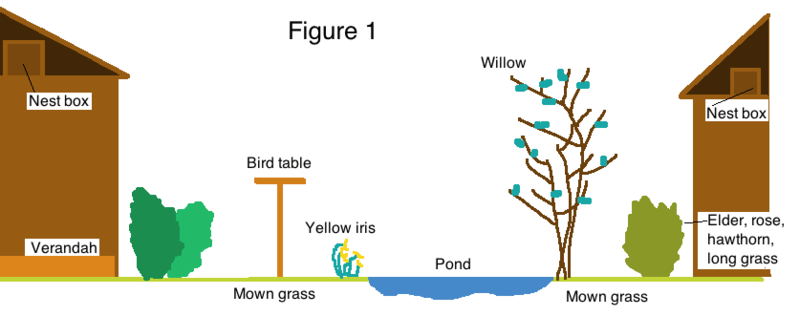

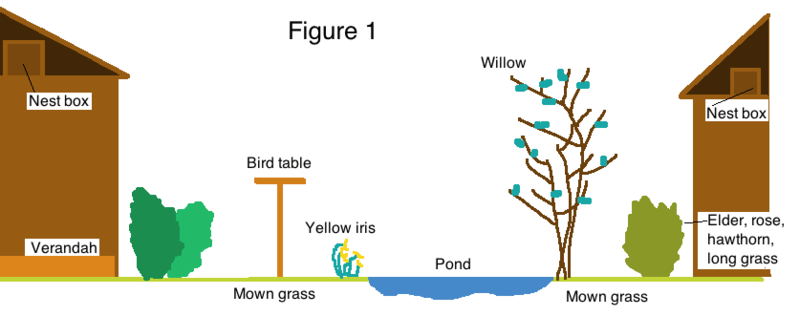

Figure 1 shows what can be done using an apparently unpromising site. Despite the veranda being used constantly throughout the day, each of the nest boxes was used successfully in one summer. By planting a few shrubs, making nest boxes in woodwork classes, and having a pond installed, the whole school benefited. Ponds are invaluable teaching resources and every effort should be made to get one established. A small, shallow pond has a lot of interest and need not be a danger, even to the smallest child.

Existing hedges can also be made a focus for development. Similarly, walls, isolated trees and boggy areas can be retained and enhanced. It is best to consider every feature carefully before starting work.

A New Site

On a new site a little skill in design may be needed; if in doubt, call in an expert. The design of new school grounds is constantly improving on the pattern of playing fields and a scattering of trees.

On a new site a little skill in design may be needed; if in doubt, call in an expert. The design of new school grounds is constantly improving on the pattern of playing fields and a scattering of trees.

Grounds away from the playing field are often unnecessarily flat, and some variety in levels is a great advantage in a wildlife area as well as being more attractive. However carefully the ground around a new building has been made-up after construction and landscaping, there are often problems in establishing good vegetation cover.

During development, topsoil is stripped from the site, stored and replaced on completion. Normally it is re-laid at about 150mm depth but the subsoil beneath this may have been compacted by heavy machinery. This causes water-logged patches and prevents good root development by trees and shrubs. The area will have a drainage system if intended for playing fields, but experts should be consulted if drainage is impaired or plant growth poor.

Soil structure is easily damaged by bad storage, or by working in wet weather when the soil particles are broken down. Clay soils are particularly prone to this. The main nutrients missing from poor soils are nitrogen and phosphate. Plants which can fix their own nitrogen, such as gorse, broom, alder, clovers and birds’ foot trefoil will grow well in such soil since there is little competition from other plants. The nitrogen accumulated in the soil by these plants builds up to become available to other species, so tree plantations with a lot of alder, and grass seed with a lot of clover are likely to be successful.

Rich soils, if not carefully managed, are usually covered by a few very vigorous plants (e.g. cocksfoot and wildoat grasses). Poor soils, especially lime-rich ones, develop a more varied vegetation because they support a lot of slow-growing species. It is essential, therefore, to use the soil to its best advantage and not add fertilisers indiscriminately. A simple soil-testing kit sold be garden centres will give a good indication of the soil’s pH status. The establishing of trees and shrubs may need some inorganic fertiliser (either a single nutrient or a balanced fertiliser) and organic matter. The latter can be obtained cheaply as sewage sludge, hop waste or farmyard manure. Areas intended for meadows can be established without the help of fertilisers – wildflowers generally prefer poor soils and a rich soil only encourages the tougher grasses to flourish at the expense of the more delicate flowering meadow plants.

Planning a Site

Before digging and planting begins, it is important to undertake some elementary surveying – a useful exercise for a number of pupils.

Before digging and planting begins, it is important to undertake some elementary surveying – a useful exercise for a number of pupils.

The underground and overhead surfaces should be marked on a plan to avoid planting too near them. In planning a layout, there should be plenty of boundaries such as those between scrub and grassland, and variety in height. Apart from their pleasant effect on the eye, such features give the greatest diversity of plants, and offer scope for all sorts of environmental studies.

Habitat areas could include spring and summer-flowering meadows, hedges, wooded area, pond, marshland, butterfly garden etc. The temptation to include too much variety should be avoided. A hotch potch will neither look attractive nor support populations of animals sufficiently large to be stable. Another common mistake is to lay out a site so that grass cutting and access from paths are unnecessarily difficult. Advice from grounds staff is essential in this case.

What to Plant

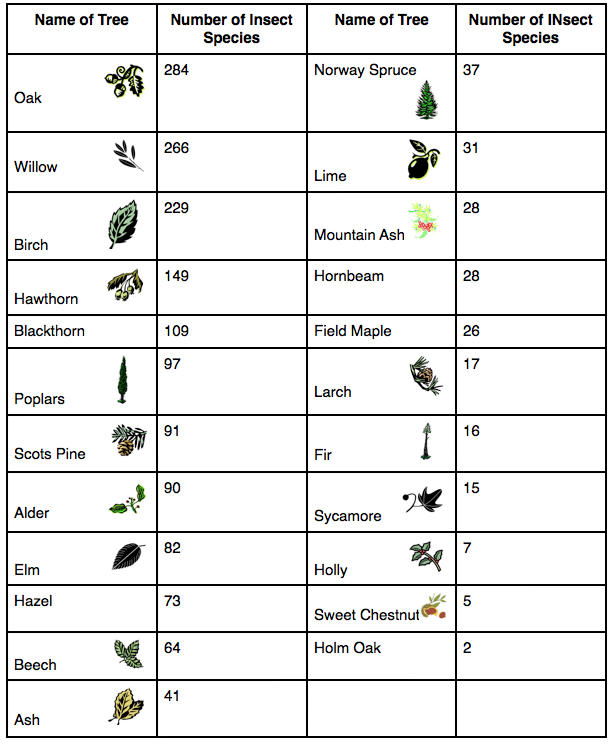

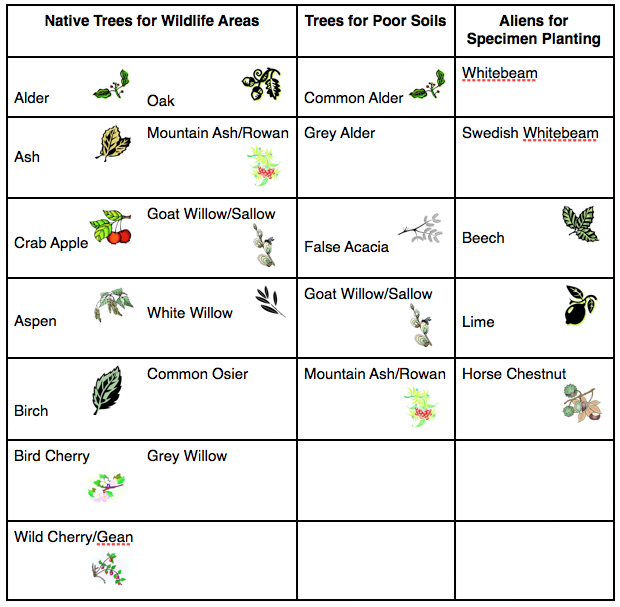

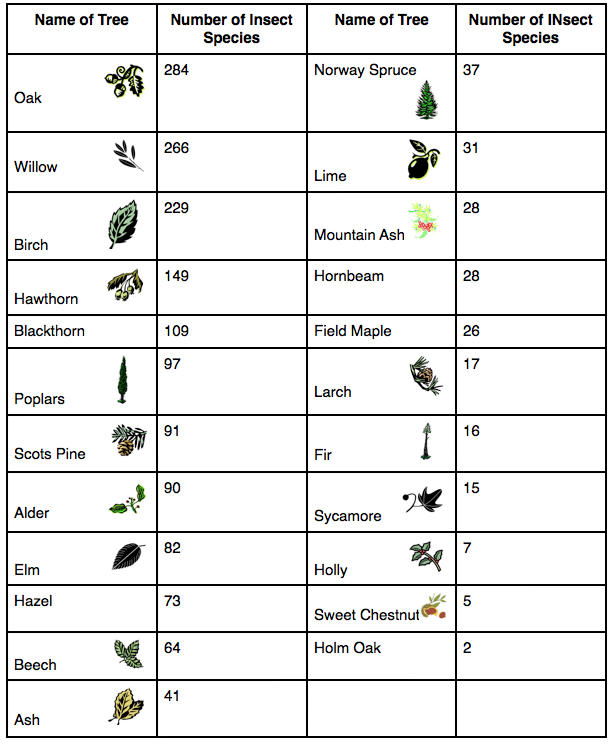

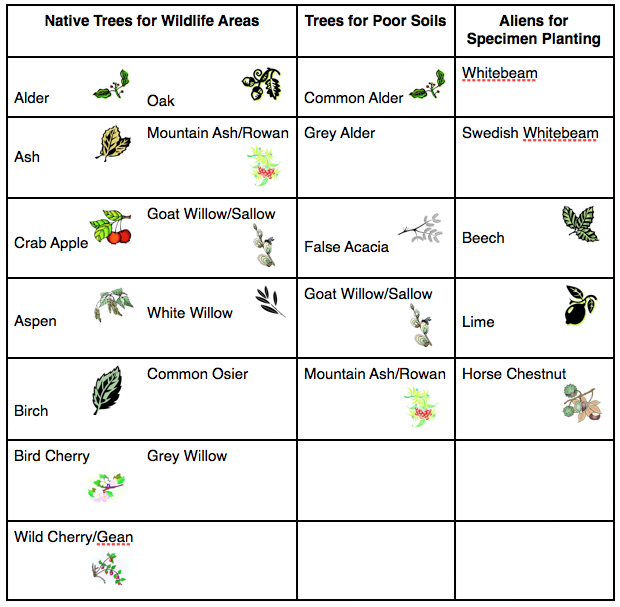

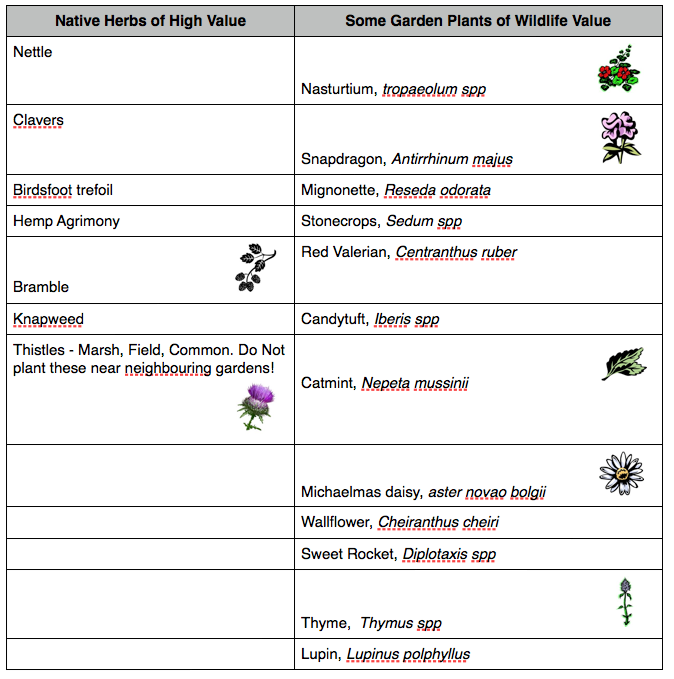

Trees and shrubs from outside this country (invasive species or 'aliens') do not have the variety of insects, fungi and other wildlife associated with them that natives have. If the aim of planting is both to educate children and to enhance wildlife in the area, native plants are to be preferred. Aliens, however, sometimes have a role in special sites. The table below, showing the numbers of insect species associated with various deciduous and coniferous trees in Britain, indicates the importance of choosing native tree species:-

Grey alder and false acacia are nitrogen fixers, suitable for dry impoverished soils. Swedish whitebeam and common whitebeam are hard, wind-resistant trees with bright red berries that provide food for birds. Sycamore is very common in many areas due to its tolerance of exposure and poor soils, but it is a very invasive tree, poor in wildlife, and should not be planted. Oak, ash, beech and lime are very big trees at maturity, and as such cause a lot of problems if too near buildings. However, there are small-growing varieties which can be obtained. Poplars and willows have very high wildlife value and grow rapidly, but have a very high moisture demand and on a clay soil give rise to shrinkage which can cause the collapse of walls. They should not be planted within 60m of any structure on clay.

Where there is room for a block of tree planting (100m square or more), it is best done on a forestry pattern. The principle of this method is that conifers such as Japanese larch, Scots pine and Sitka spruce are planted in a mixture with hardwoods, for which they act as protective nurses, and are thinned out as the plantation matures. Presented with a site, the Forestry Commission can advise on a suitable mixture.

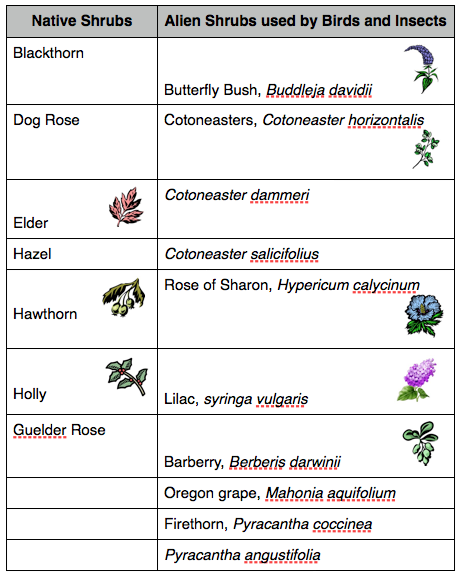

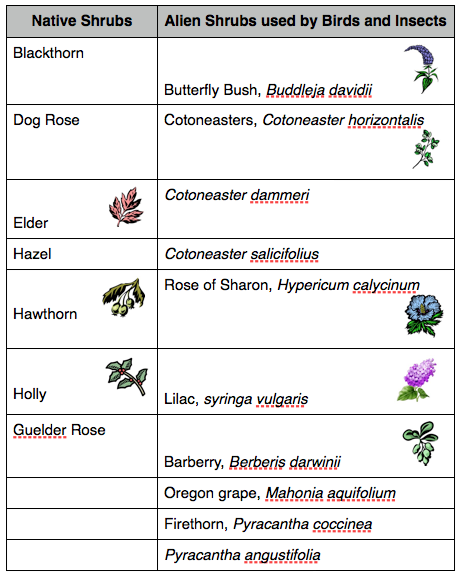

Shrubs

Many alien shrubs are good for wildlife. Pyracantha and Cotoneaster berries attract birds: Buddleia, Berberis, Mahonia, Escallonia and others attract insects. While in large scale planting it is obviously better for education and wildlife to use native species, in formal areas it is possible to choose attractive garden plants which have a wildlife value.

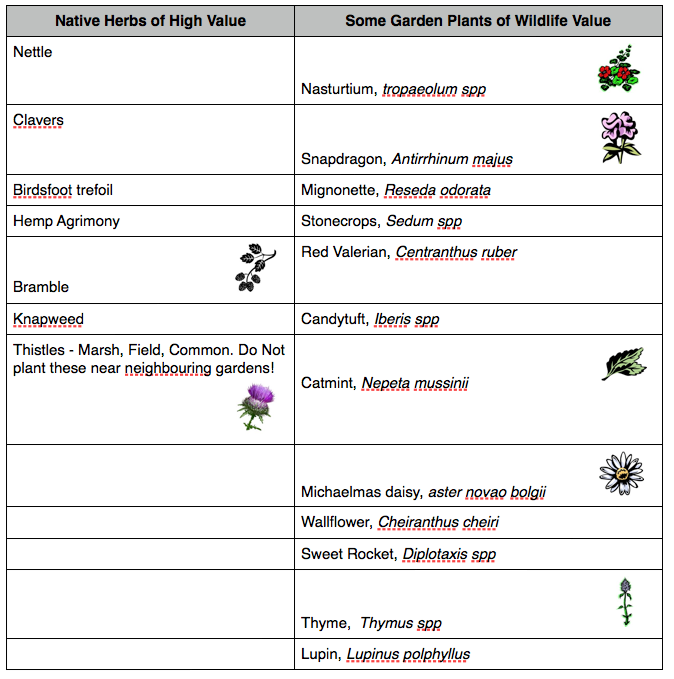

Herbaceous Plants

Native wild flowers can be cultivated by allowing them to invade after suitable treatment; e.g. rotivating an area and allowing it to run wild, or leaving strips of land next to walls and fences to become covered with bramble (an excellent wildlife plant). More challenging but more rewarding is to collect seed and establish wild flower gardens. Plants like toadflax and knapweed produce colourful flowers and large quantities of seed. It is best to find a plentiful local patch and keep an eye on it until the seed is definitely ripe. It should be collected on a dry summer’s day in paper bags so the seed is not damp. Some seed will need stratifying (storing in a sand pit during the winter) before it will germinate, some can be sown immediately. Unlike growing traditional cultivated plants there may be a lot of trial and error, but this can be turned into a series of class exercises in finding out the effect of different treatments. Alternatively, wild flower seeds and plants can be bought from a number of companies, but make sure you are buying native stock and not continental cultivated strains.

A few alien garden plants have wildlife value e.g. Michaelmas daisy and pink valerian attract insects, but others are more or less barren.

When to Plant

Generally it is best to plant as soon as the worst of the winter weather is over, in March/April. However, October/November planting of shrubs, if well done, can be successful.

Natural grouping of species

A wildlife area will be a more valuable habitat if species of plants are grouped, as they would occur naturally. For example, a natural woodland can be simulated by planting a mixture of standards, whips and shrubs to give an idea of structure. Combinations of species should be chosen by reference to what grows naturally in the area. In a mature woodland, the plants grow at different heights to form layers. Many plants and animals are most at home in the dappled shade of the woodland edge.

Further Information

For further information please visit our Roots to Green Living resources page. Would you like the Roots to Green Living scheme in your school? Contact us!

Credits

Image: Wildlife Areas for Schools - Learning Outside the Classroom by NWABR

Traditionally, school buildings have been surrounded by rather grim landscapes, particularly those in built-up areas – which account for the majority of schools in Britain. It may seem a daunting task to embark upon a development programme for transforming a square of asphalt into a richly diverse landscape with trees, ponds, flowers, seats, grass, animals etc! However, the long-term benefits of such a scheme will make all the effort involved well worthwhile.

Traditionally, school buildings have been surrounded by rather grim landscapes, particularly those in built-up areas – which account for the majority of schools in Britain. It may seem a daunting task to embark upon a development programme for transforming a square of asphalt into a richly diverse landscape with trees, ponds, flowers, seats, grass, animals etc! However, the long-term benefits of such a scheme will make all the effort involved well worthwhile. Many areas of the curriculum may be covered in the planning and making of a wildlife area. In Maths the children can solve real problems involving estimation, measuring and calculating surface areas. Map work can be undertaken, such as drawing plans and making scale drawings and scale models when designing the pond area. There are opportunities to carry out research on food chains, food webs and other principles of ecology. Some children may become interested in the conservation aspects of the project, leading to work on endangered species and the effects that humans have on the environment, such as picking wild flowers and using agricultural chemicals.

Many areas of the curriculum may be covered in the planning and making of a wildlife area. In Maths the children can solve real problems involving estimation, measuring and calculating surface areas. Map work can be undertaken, such as drawing plans and making scale drawings and scale models when designing the pond area. There are opportunities to carry out research on food chains, food webs and other principles of ecology. Some children may become interested in the conservation aspects of the project, leading to work on endangered species and the effects that humans have on the environment, such as picking wild flowers and using agricultural chemicals.

Once the site of the wildlife area has been decided on, the next stage is to apply for financial help! Head over to our

Once the site of the wildlife area has been decided on, the next stage is to apply for financial help! Head over to our

On a new site a little skill in design may be needed; if in doubt, call in an expert. The design of new school grounds is constantly improving on the pattern of playing fields and a scattering of trees.

On a new site a little skill in design may be needed; if in doubt, call in an expert. The design of new school grounds is constantly improving on the pattern of playing fields and a scattering of trees. Before digging and planting begins, it is important to undertake some elementary surveying – a useful exercise for a number of pupils.

Before digging and planting begins, it is important to undertake some elementary surveying – a useful exercise for a number of pupils.